Steve Biko died in police custody on September 12, 1977, six days after being arrested by South African police. An unauthorized (secret) autopsy revealed brain trauma caused by severe blows to the head was the cause of death.

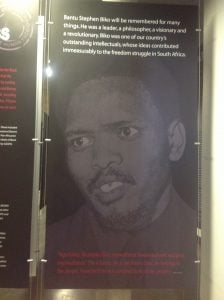

Biko was the leader of the Black Consciousness Movement, an organization that promoted liberation and political change through peaceful, non-violent means of resistance. Because Biko’s words challenged the ruling Afrikaner Nationalist Party’s apartheid government, he was considered a danger to the state and was “banned.” This meant he was on house arrest and forbidden to meet with more than one person at a time outside his immediate family. He was arrested while traveling outside his banning area.

traveling outside his banning area.

Steve Biko was a natural leader with “natural gentleness” and a “razor-sharp” intellect, a quick sense of humor. “We were drawn to him at once. Physically, he was an imposing figure, very tall, extremely well-built with a noble face. He was not an extrovert–one had the sense of a great capacity for self-containment. He spoke quietly, generally unemotionally, and all the time one was aware of his acute sensibilities–his ability to listen, to sift and make judgments on thwa tpeople were saying to know what they were really like” (211). He spoke to gatherings of people and published widely. His speeches and articles have been collected in the book I Write What I Like.

Police Commissioner Kruger announced at a press conference that Biko died after a hunger strike. Everyone who knew him knew this to be false. He had, in fact told his friends that if something happened to him, they should know he would never have taken his own life. When his announcement led to sniggering among his supporters, one even complimented him on running such a democratic system that he “allowed his detainees the democratic right to starve themselves to death” if desired. Kruger, “preening,” agreed. In response to questions, Kruger said Biko’s death “leaves me cold.” He added, “I suppose one feels sorry about any death. I suppose I would feel sorry about my own death.” The callousness of this response speaks for itself.

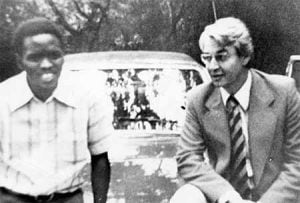

The book chronicles the relationship between journalist and newspaper editor Donald Woods and Steve Biko. Woods at first wrote rather unfavorably about the rather well-known actions and words of Steve Biko. When challenged to meet him and learn the truth before printing his stories, Woods set out to meet Biko. Drawn to him (as shown above), the two and their wives and families became friends. Woods’ stories changed. Biko was killed. Woods wrote in protest, and was himself banned. When his own family came under attack, they finally escaped the country with the manuscript of this book, narrowly escaping being killed.

The book was published in 1978, only a year after Biko’s death. It was made into the movie Cry Freedom in the late 1980s, both while apartheid was still in practice. Steve Biko became an international icon and helped move the world to sanctions against South Africa until the apartheid system changed.

In South Africa, I asked one Black man if he had read the book or seen the movie Cry Freedom. He said he had, but what he didn’t like about the movie was that it was all about Donald Woods’ story, more than about Biko’s story. This is true, I guess, though the book certainly details much more than the movie could, of course, especially transcripts from “interrogations” and court proceedings during the inquest into Steve’s death. The positive side of seeing this from Woods’ point of view is the ability to move with him through his change of heart–from a racist white South African–to a broad-minded, inclusive freedom-minded individual willing to risk his own life for the freedom of all South Africans. That transformation can affect a reader or watcher perhaps more powerfully.

I’m sick about this post. I had a lengthy treatise written about this book because I’ve been reading it for along time, and it has affected me greatly. A wrong flick of a computer key, and the entire thing disappeared. I had several more quotes in the original version, but this recreation captures the main ideas I wanted to convey.

Reading this book, walking through King Williams Town and Port Elizabeth where Steve walked, standing at his grave and spending time in the Steve Biko Museum all build into an emotional experience. Steve Biko is, and will forever be, one of the heroes of my life. BIKO!

Woods, Donald. BIKO. Essex: Paddington Press, 1978.

Subscribe To Rebecca'sNewsletter

Join the mailing list to receive the latest news and updates from Rebecca.

You have Successfully Subscribed!