“No one is born hating another person because of the color of his skin, or his background, or his religion. People must learn to hate, and if they can learn to hate, they can be taught to love, for love comes more naturally to the human heart than its opposite.”

― Nelson Mandela, Long Walk to Freedom

Mandela, Nelson. Long Walk to Freedom. 1994. Back Bay Books, 1995.

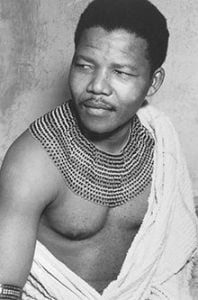

Nelson Mandela. His name has become synonymous with freedom, with justice, and with sacrifice for the greater good. “Madiba” as he is called in South Africa, has almost been elevated to the status of god. He wasn’t perfect, but if anyone deserves the kinds of honors this man has received, it’s Nelson Rolihlahla Mandela.

Long Walk to Freedom is 625 pages long (at least the copy I read is), and is an intimidating read. Had I looked more closely at my choices, I may not have piled so many thousands of pages on my reading list for the semester while also writing a novel and a screenplay. HOWEVER, I’m glad I did. I had been wanting to plow through this volume for two years. This forced me to do so.

A review can’t do this book justice. It is easy to read, in a voice that engages us and pulls us along. When I skim through it, a sentence here and there captures me and pulls me back into the story. I also want to say that the movie by the same name, based on this book does NOT do it justice. In both this instance and BIKO by Donald Woods, I saw the movie before reading the book. “Cry Freedom” based on BIKO does a good job of capturing the character and story. I do not think the movie Long Walk to Freedom does this book justice. I watched it during my sabbatical and was so disappointed, I couldn’t even write a blog review. This book is spectacular. I wish we had time and space in my South Africa class to read the whole thing. As it is, I am going to encourage my students to download or purchase the 6-hour audio book if they’re not willing to tackle the whole thing.

“Rolihlahla” means pulling the branch of the tree, which is more accurately translated from the Xhosa to mean “Troublemaker.” Maybe this name was an omen for the future. He made trouble, all right, for the governing authorities–the best kind of trouble possible. The name Nelson was given to Rolihlahla on his first day of school; all children were given English names, which is why, he says, that most people from his generation have both English and African names (14). “Nelson” stuck, but when Scott Fee and I were having dinner with a family in Khayelitsha Township (TRIPE, by the way), Mandela had not yet been admitted to hospital in 2013. We were talking about Madiba, and one of the older women said fiercely to me, “‘Rolihlahla’ is Madiba’s name!” And she made me practice until I could say it sounding like a true Xhosa.

Madiba was recognized early as being exceptionally bright. He was privileged since his father ruled Thembuland and was an advisor to kings. His early influences included stories by his father about Xhosa heroes and legends and folktails from his mother. He watched leaders who were respected and said the best leaders “led from behind” “like shepherds”(22). They motivated their people to action but didn’t need to be front and center to take credit. This lesson stayed with him throughout his life. Later he said, “I never cared very much for personal prizes. A man does not become a freedom fighter in the hope of winning awards, but when I was notified that I had won the 1993 Nobel Peace Prize jointly with Mr. de Klerk, I was deeply moved” (611). He joined Chief Luthuli and Desmond Tutu as South African recipients of this prestigious award. Still, Mandela deflects the praise, saying the award was for all South Africans who had fought in the struggle; he would “accept the award on their behalf” (611).

Mandela’s story is epic. The arc collaborates Michener’s Covenant that I recently read, and corraborates Michener’s ability to show the African’s side of the story, not just that of the white Afrikaner. One example that pulled at my heart was his description of Dingane’s Day–a holiday in South Africa. The Afrikaners celebrate it as the stunning victory over Zulu king Dingane at the Battle of Blood River in 1838. Afrikaners celebrate it as a demonstration that God was on their side. Africans mourn the day as the massacre of their people. Mandela and other ANC leaders chose this day as a day to protest apartheid and sabotage power stations and government offices. “Death in war is unfortunate, but unavoidable.” Although Mandela is known as a leader in non-violence, the leaders of the ANC realized that a complete absence of violence had only let their subjugation continue. (This is not unlke Steve Biko punching back when police officers started hitting him during interrogation) (284-285).

Humor runs through the book, too. He shares how Chief Luthuli, a “Cangerous agitator at the head of the Communist conspiracy” was chosed to receive the Nobel Prize in Oslo. He was given permission to leave the country for ten days to do so. “Afrikaners were dumbfounded; to them the award was another example of the perversity of Western liberals and their bias against white South Africans” (284). Another example is Eddie, one of his friends on Robben Island, tiptoeing to the podium during a lengthy, lofty Sunday morning prayer, and stealing the day’s newspaper from the visiting preacher’s briefcase (453).

Mandela’s story shows what true compassion and determination can do. The book reveals traditional Xhosa life, his circumcision at sixteen, being a boxer, becoming a lawyer, fighting relentlessly against the evils of apartheid, his devotion to the ANC (African National Congress), his determination to educate his children in order to keep the minds unshackled by oppression, boycotts, protests, arrests, his first marriage, meeting Winnie and falling in love with her, his participation in the “guerilla army,” charges of high treason, the infamous Treason Trial, his eventual imprisonment, and a colorful but tragic revelation of life in prison in Pretoria, being moved to Robben Island, all while classified among the most dangerous, highest security prisoners. Mandela wrote most of this book while in prison on Robben Island. Small victories for prisoner were part of his experience and his leadership role.

Mandela’s eventual move to Victor Verster Prison on the mainland, just outside of Cape Town, was his final stop in prison. There, he and President deKlerk met in secret and hammered out the terms of his release and negotiated ways to end apartheid without a civil war. He lived in a four-bedroom cottage, still isolated from other prisoners, but treated with a measure of respect. (See post with pictures from July 15 about the movie “The Color of Freedom”). My students and I visited this home, sat at Mandela’s table and on his furniture even though this house is not open to the public yet.

Mandela’s more recent life is more widely known. The movie “Invictus” demonstrates the kind of president he was after elected in 1994 at the first one-man-one-vote election in South Africa. The section of the book titled “Freedom” begins only on page 559. His casting his first vote in the aforementioned election is on page 617. I imagine that once out of prison, he was too busy to write as much. But some of his memorable and far-reaching statements are included in this section. “…I knew that the oppressor must be liberated just as surely as the oppressed. A man who takes away another man’s freedom is a prisoner of hatred, he is locked behind the bars of prejudice and narrow-mindedness. I am not truly free if I am taking away someone else’s freedom, just as surely as I am not free when my freedom is taken from me. The oppressed and the oppressor alike are robbed of their humanity” (624).

At any rate, this epic volume demonstrates the horrific outcomes of a diabolical government that seeks to subjugate a group of people. Apartheid may be considered one of the most enduring despotic violent systems of oppression in world history. The fight of brilliant people behind the scenes and sometimes center stage to end it is the heart of this story. If you are a fan of Nelson Mandela, this book is a must. I intend to listen to the abridged 6-hour audio version, too, to refresh myself, and to see if it’s worth recommending.

When “Madiba”–Nelson Rolihlahla Mandela retired from the South African presidency, President Clinton said the following:

“In every gnarly, knotted, distorted situation in the world where people are kept from becoming the best they can be, there is an apartheid of the heart. And if we really honor this stunning sacrifice of twenty-seven year, if we really rejoice in the infinite justice of seeing this man happily married in the autumn of his life, if we really are seeking some driven wisdom from the poser of his example, it will be to do whatever we can, however we can, wherever we can, to take the apartheid out of our own and others’ hearts.” This 600+ page book is his story, and it makes clear why this is true.

Subscribe To Rebecca'sNewsletter

Join the mailing list to receive the latest news and updates from Rebecca.

You have Successfully Subscribed!