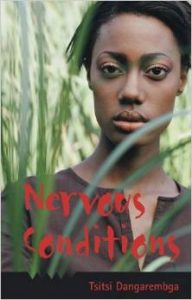

I’ve had this book in my to-read pile since I started collecting African literature. It’s an interesting read, and I highly recommend it to those interested in women’s literature from Africa. I certainly would use this book if I taught an African lit. class. I’d also use it if I ever get to teach Women’s Lit again.

Since it’s set in Zimbabwe (called Rhodesia at the time the story is set–60s and 70s), it’s not appropriate for my South Africa class, and I already have too many African novels that I want to teach in World Lit and Film. HOWEVER, this is a worthy read, and it would make for fascinating discussion in class.

Western Michigan has a terrific discussion of this book here.

This story is semi-autobiographical, and it rings true in a way that such stories do. There’s something about an autobiographical novel that inserts some details or insights that may be unbelievable in straight fiction but are necessary in stories based on real lives. (Examples that come to my mind immediately are Dorthy Alison’s Bastard out of Carolina, Maya Angelou’s I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings, and Bryce Courtenay’s Power of One). All of these stories require a tiny suspension of disbelief–that a person could be so cruel; that a person survived what he or she did or had the insights he/she did at such an early age–but all demand acceptance of the “Because it is true” unspoken clause behind the story. In straight fiction, we can’t get by with that; if there’s a false note, we get busted. Autobiographical fiction has its on genre, it seems. And we forgive more because we demand so much from a “true” story like this, even when it claims to be fiction.

This story is semi-autobiographical, and it rings true in a way that such stories do. There’s something about an autobiographical novel that inserts some details or insights that may be unbelievable in straight fiction but are necessary in stories based on real lives. (Examples that come to my mind immediately are Dorthy Alison’s Bastard out of Carolina, Maya Angelou’s I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings, and Bryce Courtenay’s Power of One). All of these stories require a tiny suspension of disbelief–that a person could be so cruel; that a person survived what he or she did or had the insights he/she did at such an early age–but all demand acceptance of the “Because it is true” unspoken clause behind the story. In straight fiction, we can’t get by with that; if there’s a false note, we get busted. Autobiographical fiction has its on genre, it seems. And we forgive more because we demand so much from a “true” story like this, even when it claims to be fiction.

At any rate, this book has been considered a classic African woman’s novel since long before I opened it, or even heard of it. This is the personal story of struggle between westernization and adhering to family and traditional values, especially when those family values themselves have been westernized and Christianized beyond recognition in many ways. The most westernized character in the story, Nyasha, is protagonist Tambudzai’s cousin and confidante. Nyasha struggles with inability to respect her father when he has both forced her to live in England and return to “traditional values” that have become almost entirely Christian values, yet forced into the African way of life–not a comfortable fit.

The struggle is deep and complex and symbolizes and verbalizes the ongoing struggle in Africa, particularly for women. Dangarembga depicts this lyrically; even though sometimes the exposition gets a big pedantic, we as readers simply don’t care. We go with the story. Dangarembga herself spent some of her formative years in England before returning to then Rhodesia. The author has divided her own experience into that of two young women instead of just one. This brilliant move allows us to discover the identity-culturual struggle through the eyes of a young girl who has never left her home, but comes to love her cousin who has seen a bigger world and won’t settle for the world being only one way.

I recommend it. It’s only a bit over 200 pages, and well worth the time.

Subscribe To Rebecca'sNewsletter

Join the mailing list to receive the latest news and updates from Rebecca.

You have Successfully Subscribed!